The Control Paradox

Your agent orchestrator probably gives you less control than you think.

The setup

Here's a scene that plays out in engineering organizations everywhere: a team decides to use AI agents for large-scale refactoring across their codebase. Hundreds of repos. Thousands of files. The kind of work that would take a human team years.

Let's call this kind of cross-repo effort a campaign: a named initiative with a defined scope, tracked state, and a finish line.

And then someone says the magic words: "we need a pipeline".

Of course we do! We're engineers. We build pipelines. We've been building pipelines since Jenkins was just a glimmer in Kohsuke Kawaguchi's eye. Clone, build, test, transform, verify, PR. Steps. States. Transitions. This is our comfort zone.

So the team goes off and builds what I'll call the Narrow Context Pattern: a deterministic state machine that drives an AI agent through discrete steps. The agent gets called at specific points with prompts like "fix this build error" or "migrate this API call", but the orchestrator holds the reins. The agent sees only what we show it. The pipeline controls the flow.

It feels safe. It feels engineered.

And here's the paradox: by taking control away from the agent, we often get worse outcomes.

Iron Man vs. Ultron (but not how you'd expect)

Tom Limoncelli wrote a fantastic piece called Automation Should Be Like Iron Man, Not Ultron. The thesis is essentially that automation should collaborate with humans, not replace them. Ultron-style automation runs autonomously until it hits a wall, then fails catastrophically. Iron Man-style automation keeps humans in the loop, empowering them to do more while staying in control.

Most people read this and think: "Right, so we should constrain our AI agents. Keep them on a leash so we understand what they're doing. Pipeline-driven orchestration = Iron Man".

They have it exactly backwards.

The Narrow Context Pattern is Ultron in disguise.

When the pipeline fails at step 47 of 52, what are your options? In practice: retry or restart. Yes, some pipelines offer checkpointing and partial reruns. But even those only preserve outputs, not reasoning. The agent has no memory of the decisions made in steps 1-46. It was a hired gun, called in for specific jobs, dismissed after each one.

There's no collaboration. There's no graceful recovery. There's just "try again".

Meanwhile, an agent that understands the overall goal, has visibility into its own history, and can reason about the entire campaign can say "step 47 failed because of a decision I made in step 12, let me reconsider". It can collaborate with a human who drops in to help. It can adapt.

That's Iron Man. The suit enhances Tony Stark's judgment. It doesn't replace it with a rigid flowchart.

The complexity cliff

I've taken to calling the failure mode implied by Limoncelli's thinking the complexity cliff: automation that works until it doesn't, and when it fails, it fails completely. No middle ground or partial success.

This is important because it changes how you reach for the tool. Before you run it, you have to estimate the probability of success. If that probability is low, you don't bother. The cliff limits usefulness before you even start.

Pipeline orchestrators hit this cliff hard. Not because they're poorly built. Often they're beautifully engineered, with retries and caching and telemetry. But they fail anyway, because their fundamental model doesn't scale to genuine novelty.

Consider: you've built a migration pipeline that handles 90% of cases elegantly. The remaining 10% are edge cases. So you add conditionals. Exception handlers. Special-case steps. Your clean state machine accumulates complexity like sediment.

Now something truly novel happens. A repo with a structure no one anticipated. A build system that violates assumptions.

Your Ultron falls off the cliff. The agent that made the decisions is long gone. Its context evaporated after each step completed. And because Ultron-style automation treats failure as exceptional, not expected, there's no graceful recovery path; engineers stare at logs trying to reconstruct what happened, quickly give up, and do the work by hand.

Early in our experimentation, we built exactly this kind of system. It worked at small scale for a handful of repos and simple transformations. We thought we were being rigorous. We thought deterministic control meant predictable outcomes. What we discovered was that we'd given the orchestrator too much responsibility and the agent too little context. At scale, the narrow context pattern produced locally reasonable but globally suboptimal decisions. The agent would try to do exactly what we asked in each step. However, without visibility into the overall goal it couldn't course-correct. It couldn't reuse prior investigation. It re-reasoned about how to compile each time. Small issues compounded and frequently the agent failed or gave up.

Persistent task tracking

The core problem with the Narrow Context Pattern is that context evaporates between steps—the agent can't reason about what it did or why.

So what's the alternative? Let the agent run wild? Full autonomy, hope for the best?

No. That way lies what some have affectionately called "agent chaos at scale". Pure autonomy can work if you have senior engineers willing to heroically untangle the wreckage each time. But heroics don't scale. Production systems need predictable recovery, not individual brilliance.

The answer is an emerging pattern that others have arrived at independently: let the agent decompose its own work, but persist that decomposition outside the context window. This solves the core problem: the agent retains goal visibility and decision history even across restarts, without the context rot that comes from endless conversations.

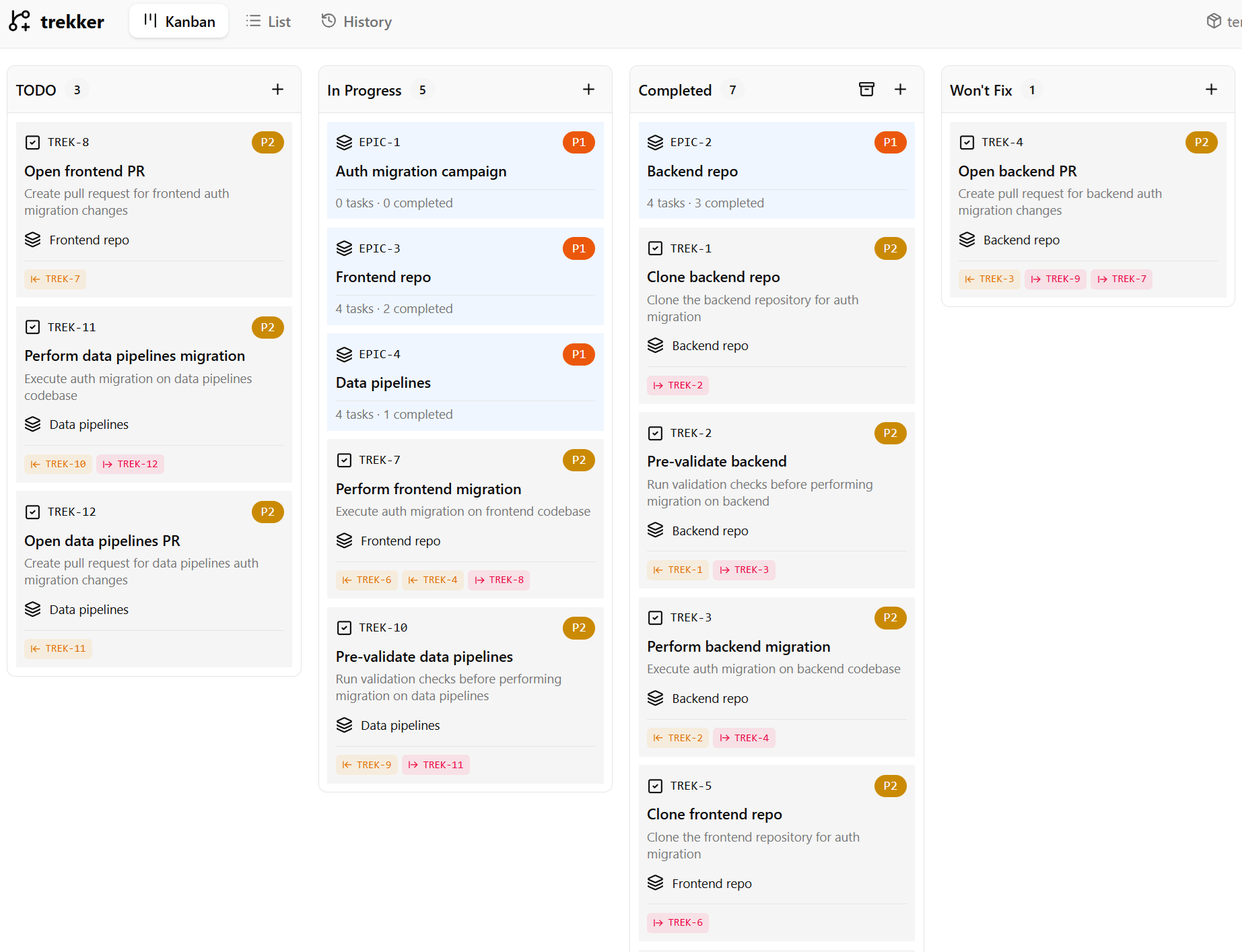

Tools like Trekker create a simple SQLite db of issues with a CLI interface. The agent can easily query "what's ready to work on". The Ralph Loop takes a complementary approach: spawn a fresh agent instance per iteration, with state persisted to filesystem and git. Each agent reads the current state, does a unit of work, updates the state, and terminates. No context rot. No compounding errors from long conversations.

Isn't this where we started?

At first glance, it might sound like we've come full circle to the Narrow Context Pattern I was criticizing to begin with. Both involve discrete units of work. Both persist state externally. But the key difference is who's driving.

- Narrow Context Pattern: External orchestrator drives the agent, feeding it one task at a time. The agent focuses because it literally cannot see anything else.

- Persistent Task Tracking: The agent maintains visibility into the overall goal while working on specific tasks. It focuses because it chooses to, with the full campaign in view.

Same practical effect (focus on immediate work), completely different reasoning dynamics. What makes persistent task tracking work:

- Agent owns work breakdown: The agent decomposes goals into tasks, not externally imposed by an orchestrator

- Persistent tracking outside context: Task state lives on outside chat history

- Goal visibility: The agent can always see the overall objective and remaining work, giving it a trajectory

- Explore, then preserve: The agent can fork, experiment, and backtrack where only the chosen path is persisted. This works better than simple context compaction. I saw repeatedly that agents that could explore and backtrack produced better diffs than agents with a single, longer exploration that experienced compaction. Whether this is about preserved optionality or something deeper about how models reason, I don't know.

We discovered this need through trial and error. Before adopting persistent task tracking, the agent would wander aimlessly and make "careless mistakes" like cloning repos to different locations between iterations, losing track of its work, etc. Giving it an external driver didn't help either; the agent would reason correctly on each narrow step, but lose that reasoning on the next iteration. Each restart compounded failure risk. When we gave the agent persistent task tracking, something shifted. It stopped wandering. It could reason about whether its current action served the larger purpose.

Persistent task tracking also enables the Iron Man collaboration we actually want:

- A human can see what the agent is working on

- A human can resume a failed campaign with context intact

- A human can adjust goals mid-flight without starting over

- Multiple agents or humans can collaborate on the same campaign

When you inevitably encounter a novel situation, Iron Man helps you calculate a new path. Ultron just crashes.

Where to draw the line

I don't know exactly where the line should be drawn between agent autonomy and deterministic control. I don't think anybody does yet. But I'm increasingly convinced it's closer to the agent-native end than most engineers assume.

Here's a framework for thinking about it:

Give to the Agent

- Goal visibility: The agent should always know why it's doing what it's doing

- Decision authority over approach: If there are multiple ways to accomplish a task, let the agent choose

- Recovery and adaptation: When things go wrong, the agent should be first responder

- Context accumulation: History of decisions, not just history of outputs

- Sandbox execution: Let the agent own execution within the sandbox—filesystem, local git operations, build and test, design and work breakdown, retry loops, and flagging tasks as blocked

Avoid stripping ambient state by driving the agent externally step-by-step, or hiding what tasks remain. The agent needs that visibility to reason effectively.

Keep in deterministic control

- Irreversible external effects: Use policy, via hooks or a broker, for operations with side effects (force-push or PR creation) and resource enforcement

- Verification gates: Agents will claim success without evidence. Make verification blocking, not advisory. No PR without passing tests, no "done" without proof.

- Concurrency boundaries: Which repos are being worked on, lease management, preventing conflicts

- Audit trail: What happened, when, what state resulted, and full reasoning and tool call logs

- Resource limits: Timeouts, token budgets, iteration caps

Don't let the agent mutate campaign scope. It can mark tasks blocked; only the harness can abandon them. The agent proposes, the harness disposes.

The risk framing matters

Here's what makes agent orchestration fundamentally different from the ops automation that Limoncelli was writing about: before opening a PR, mistakes are cheap.

We're not doing ops work. Nothing is unrecoverable. If the agent clones a repo wrong, clone again. If it generates bad code, regenerate. If it goes down a blind alley, backtrack. The entire pre-PR phase is a sandbox. We can afford way more agent autonomy than our ops-trained instincts suggest. The place to be rigorous is at the moment of irreversible effect, not in the exploratory work that precedes it.

Lessons Learned

The opinions above emerged from experimentation. Here's surpising patterns and mistakes made more than once.

On Focus

- Agents struggle with repetition. Ask an agent to "do this in 10 places" and it does it in 5. Ask it to "do this in one place" ten times and it gets all ten. Sequential focus keeps the work coherent.

- External task tracking (visible to the agent) is remarkably effective. It provides a vector to reason against that prevents drift.

- The narrow context pattern achieves focus by restriction. Persistent task tracking achieves focus by goal-visibility. The latter produces better decisions.

On Collaboration

- A ledger or persistent record of what's been done and what's pending enables collaboration in ways traditional pipelines cannot.

- When a human can see agent state and resume from where it left off, the whole system becomes more robust. Failures become pauses, not restarts.

- Claude Code / Copilot plugins are underrated for collaboration. They let teams share capabilities across workflows, enable reuse between engineers, and bridge the gap between "works on my machine" and "works at scale". That bridge shrinks the complexity cliff; you can test a plugin locally on one repo and gradually scale up.

On Debugging

- Debug logs make agent behavior auditable. But there's a difference between auditable (what happened) and interpretable (why it happened).

- LLM-as-judge patterns are useful for evaluating outcomes. Have a separate agent analyze the work, reflecting on the original prompt and the diff to assess alignment.

- When the agent fails consistently, feed it its own debug logs and ask "what went wrong" to produce surprisingly useful meta-analysis (but don't trust it blindly).

On Nondeterminism

- We used to worry a lot about agent nondeterminism. What we discovered is that it matters less than we thought for coding work, and matters enormously for testing. The solution isn't making agents deterministic, it's accepting nondeterminism for execution and relying on robust, automated testing.

- An LLM pretending to be a state machine is not a state machine. Do not confuse it for one.

On Cost

- The economics have shifted. At ~$0.08/iteration for meaningful work, the cost of agent orchestration is noise compared to developer time. I suspect this will change in the future, but for now it's true.

- The real cost isn't tokens, it's iteration time when things go wrong. Focus on improving iteration times.

Coming full circle

Most engineers orchestrating agents default to deterministic control because that's how we've always built automation. We extend our mental models from CI pipelines and workflow engines. This isn't distrust of AI but rather the path of cognitive least resistance.

But this framing carries hidden costs:

- Agents make locally reasonable but globally suboptimal decisions

- Recovery from failure means restart, not resume

- The complexity cliff looms as edge cases accumulate

Ceding control to the agent offers an alternative: give agents goal visibility and a vector to reason against while keeping deterministic control over irreversible effects. Focus through purpose, not through blindness.

The control paradox: sometimes you get more control by giving it away.

What Now

If you're convinced (or at least curious), here's how to put these ideas into practice. I've split recommendations by audience: practitioners building on existing tools, and toolmakers shaping what comes next.

For practitioners

Start with sandboxing. Think about isolation early as it can be painful to retrofit. Use the built-in extension

points where possible. PreToolUse hooks can prevent side effects without the pain of full containerization.

Adopt persistent task tracking. Don't reinvent this. Tools like Trekker exist. Pick one or build something similar, but get task state out of the chat history and into something durable. This is how you avoid the complexity cliff.

Resist the urge to parallelize everything. Serial focus beats parallel chaos. Your agent will thank you (or at least stop skipping steps).

Remember: pre-PR mistakes are cheap. Don't over-engineer the exploratory phase. Save your rigor for the test loop.

Use LLM-as-judge for evaluation. When work finishes (or fails), have a separate agent step in to judge. Feed it the original prompt and diff and ask "did this accomplish the goal"? Require signoff before the task can advance to the next state.

Separate tool brand from campaign brand. If you're running refactoring campaigns for many engineers, one poorly-conceived campaign can teach your users that the tool produces slop. Reviewers start ignoring your PRs. Engineers stop proposing campaigns. Make sure they know the difference between "this campaign was bad" and "this tool is bad".

Think about composability. Create packages with vertical skills. Skills explain how to do something and should work in any context. The prompt provides the policy or decision framework for how to leverage the skill in a particular context.

For toolmakers

Allow hooks to mutate, not just observe. Claude Code generally gets this right. PreToolUse should be able to

rewrite commands. UserPromptSubmit should be able to inject context. For example, it should be possible with a hook

to add --reference-if-able to git clone commands to use a local cache automatically.

Consider a "hermetic mode". Large scale refactors need to isolate themselves from machine state like user instructions and other configuration. It should be possible to create a "profile" that specifies the installed instructions, tools, skills, etc. Anything not listed should be disabled for the session.

Expose task state as a first-class primitive. The current TodoWrite tools are inadequate for proper supervision. Make it easy for agents to know what's done, what's pending, and what's blocked. Make it easy for humans to see the same thing. Allow it to persist across sessions.